To spot breast cancer early, there are mammograms. To find colon cancer early, there are colonoscopies. But there is no standard test to detect early cases of pancreatic cancer, before cancer cells have spread and when surgery is more likely to be helpful.

Finding pancreatic cancer early could help increase a patient’s chances of survival. Although pancreatic accounts for just about 3% of all new cancer cases in the United States, it’s the third leading cause of cancer deaths and is projected to become the second leading cause of cancer deaths by the end of this decade.

Across the United States, research teams are investigating ways to spot early cases, with many turning to blood-based liquid biopsy tests.

“This term ‘liquid biopsy,’ essentially, is trying to find markers in the blood that signify a tumor is present – and there are many different ways to do that. There are a lot of different features of a tumor that can end up in the blood that you could use,” said Dr. Brian Wolpin, director of the Gastrointestinal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, whose laboratory has done work in this area.

But many studies investigating the potential of liquid biopsy tests for the early detection of pancreatic cancer are still in the early phases. And the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against screening for pancreatic cancer in adults who are not showing symptoms, especially because there is no established method or test to detect this form of the disease early in the general population.

Although there currently is no single recommended blood test to find early pancreatic cancers, “there is a large scientific community working to try to change this and to identify a screening test that we can use in the clinic, but it’s quite hard,” Wolpin said. “There’s still more work that needs to be done to get there.”

One team presented its research Monday at an annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, detailing the development of a liquid biopsy test that was found to detect 97% of stage I and stage II pancreatic cancers in hundreds of volunteers. The researchers are from the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center and other institutions around the world.

Their study, which has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal, included 984 people, some healthy and others with pancreatic cancer, based in Japan, the United States, South Korea and China.

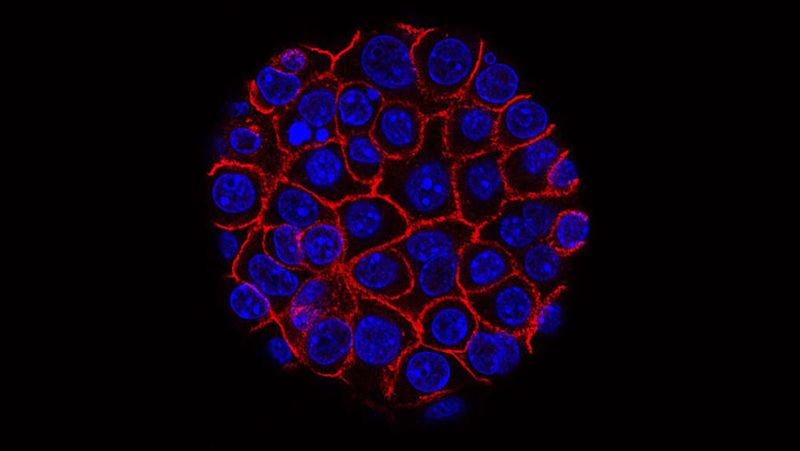

The researchers collected blood samples from each person and tested the expression of a set of small genes called microRNAs within the blood and encapsulated within exosomes found in the blood. Exosomes are small vesicles that are shed by both cancerous and healthy cells in the blood.

“Cancer cells tend to release many, many more exosomes compared to our healthy cells because our healthy cells do not multiply as fast as cancer cells do,” said Dr. Ajay Goel, senior author of the study and the chair of the Department of Molecular Diagnostics and Experimental Therapeutics at City of Hope. “And once these exosomes are released by the tumor cells, they circulate in our bloodstream.”

Goel and his colleagues identified eight microRNAs found in exosomes that are shed by cancerous cells in the pancreas and five microRNAs in blood. They used those markers to develop an approach for determining whether a person’s exosomes are associated with pancreatic cancer.

The researchers found that their liquid biopsy approach detected 93% of pancreatic cancers among the US volunteers in their study, 91% of pancreatic cancers in the South Korean cohort and 88% of pancreatic cancers in the Chinese cohort.

The researchers ran their tests again and, this time, not only used their exosome-based markers but also tested for a key protein called CA19-9, known to be associated with pancreatic cancer. When they combined their approach with CA19-9 testing, they were able to accurately detect 97% of stage I and stage II pancreatic cancers in the US volunteers.

“That’s what we are excited about: that not only this test worked beautifully in all stages, but it is 97% accurate in finding those who have either stage I or stage II disease,” Goel said.

He added that the test presented false positive results for stage I and II pancreatic cancers at a rate of less than 5%, the study data showed.

“It’s very important to diagnose the disease at the earliest possible stage, like stage I or II disease, which means there is a higher chance that the cancer is operable surgically,” Goel said. “The best cure for a pancreas patient is not chemotherapy or drugs but to take the cancer out.”

Surgeons may be “very reluctant” to operate when someone has stage III or IV pancreatic cancer, he said. That’s sometimes because of the complexity of such a procedure, the long-term complications and the likelihood that surgery at that advanced stage may not be enough to prevent the cancer from coming back.

“That’s why it is very important that this blood test is so good that it can, 97% of the time, find the cancers at the earliest possible stages where we can intercept the cancer, where we can intervene, and we can surgically remove this cancer effectively,” Goel said.

‘We need to do something’

There are blood-based tests for pancreatic cancer that are used in medicine, but they’re often used in people who have already been diagnosed with the disease. Doctors might repeat blood tests during and after treatment to determine how the cancer is responding. But there is no blood test that can detect early pancreatic cancer.

Goel and his colleagues wrote in their abstract that their approach “can potentially be further validated for clinical use in the near future,” specifically for the early detection of pancreatic cancer.

“We were generally excited about these particular data, because the cancer type we’re looking at here is extremely lethal,” Goel said.

“The number of people who are going to be affected with this disease or this cancer is going to continue to go up,” he said. “So we need to do something about it, and that is why we were extremely excited that we have a blood-based liquid biopsy for early detection of pancreatic cancer with this high sensitivity.”

The liquid biopsy test study that Goel and his colleagues presented is “interesting,” Wolpin said, and describes one approach to possibly developing a test for early detection – where there is a big need.

Definitively diagnosing someone with pancreatic cancer can involve a series of scans, blood tests and biopsies, which are typically performed only once someone has symptoms, which may include jaundice or yellowing of the eyes and skin, weight loss, belly or back pain, or tiredness and weakness. But by that point, the cancer is probably advanced.

“The vast majority of patients who present with pancreatic cancer have advanced disease at the time of their diagnosis. So 80% or more of patients present with advanced disease where we know at the time of their presentation, we’re very unlikely to be able to cure the cancer,” Wolpin said.

“That’s very different than many other of the major cancer types like breast cancer or colorectal cancer, where the vast majority of patients actually present with early disease,” he said. “The symptoms from pancreatic cancer are generally less specific, like some abdominal discomfort or sometimes weight loss – things that often don’t immediately trigger people to go to their doctor.”

But some experts warn that mass testing of average-risk healthy people who are not showing symptoms could lead to false positive results, doing more harm than good.

‘The pancreas is a very weird organ’

The City of Hope researchers are not the only scientists hoping to develop a reliable test to diagnose pancreatic cancer patients as early as possible.

In 2020, a study from the University of Pennsylvania found that a blood test to screen for certain biomarkers associated with pancreatic cancer was 92% accurate in its ability to detect disease.

In 2022, a pilot study from researchers at UC San Diego and other institutions found that a blood test to detect proteins associated with cancer cells was able to identify 95.5% of stage I pancreatic cancers among a sample of more than 300 volunteers, among whom 139 were cancer patients and 184 were healthy people.

In general, the field of pancreatic cancer is an area where there has not been much advancement when it comes to either early-stage or advanced disease, said Dr. Al Neugut, a medical oncologist at Columbia University’s Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center and professor of epidemiology at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, who was not involved in any of the liquid biopsy testing research.

“Pancreatic cancer is the poster child for cancers we’ve gotten nowhere with,” Neugut said.

“The pancreas is a very weird organ, and it’s just different than every other organ in the body,” he said. “It’s behind the abdomen, so it’s hard to get to. It’s not easy for a surgeon. It’s not easy for an oncologist. It makes it very difficult even to approach. You can’t examine it physically. It’s hard to get to radiologically. It’s hidden.”

Although pancreatic cancer is rare, people can lower their risk by eating a healthy diet, maintaining a healthy weight, getting regular exercise, avoiding alcohol, limiting exposures to carcinogens and not smoking.

“Smoking is the most important avoidable risk factor for pancreatic cancer,” according to the American Cancer Society.

Still, having some form of test to detect pancreatic cancer early would “dramatically change the landscape” for patients, Wolpin said, adding that he hopes the medical field can achieve developing such a tool.

“The more patients we can find early, the greater the chance we have to cure patients of pancreatic cancer and start to reverse the statistics that are pretty tough – almost 90% of patients who get pancreatic cancer die from their cancer,” Wolpin said. “We really need to change those numbers, and finding the cancer earlier would be a dramatic way to do that.”