In the last couple years, Houston Women’s Reproductive Services scaled down from nearly 5,000 square-feet to an 800-square-foot location. The Texas clinic cut more than a dozen full-time employees down to a medical director and three part-time staff members.

It’s no longer able to provide abortions, but it changed its focus and stayed open.

“I was willing to make whatever sacrifices needed to be made to keep our head above water, just keep the doors open and the lights on, and be able to provide care to these people who desperately need our help,” said clinic administrator Kathy Kleinfeld.

It’s one example of the shift to the the country’s abortion landscape since the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision ended the federal right to abortion two years ago. Since then, 14 states have near-total bans on abortion. Clinics can no longer provide abortions in more than a quarter of US states.

Although the total number of facilities that provide abortions in the United States hasn’t changed that much – only a couple dozen clinics have closed completely – the number of closures doesn’t always capture the upheaval.

States that enacted abortion bans generally had few clinics to start with. Since Dobbs, some packed up and moved to places where they can still provide care, but may require patients to travel further. Still other clinics remain open, but in a different capacity.

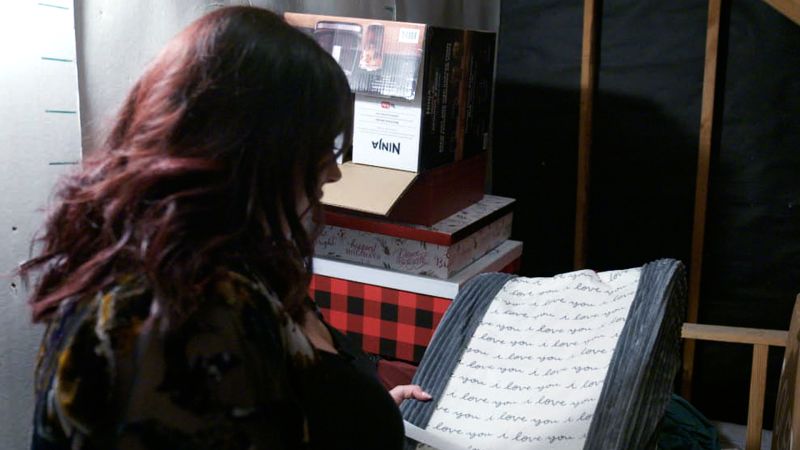

Kleinfeld’s clinic in Houston pivoted to broader reproductive health, including pre- and post-abortion care for those who travel out of state or self-manage their abortions.

In the months before the Supreme Courts’ Dobbs decision, there were about 3,000 abortions a month in Houston and Kleinfeld said she knew that need wouldn’t stop once Texas’ trigger law banned abortions.

“There were a lot of different ways it could have gone; most of all would have involved closing,” Kleinfeld said of her clinic in Houston. “That was just not something I was willing to do.”

Few clinics to start with

In 2021, there were about 750 abortion clinics in the United States, according to data from the University of California San Francisco’s Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health. Less than a tenth – only about 60 of them – were in the 14 states that have since banned abortion.

“The reason that banned states did not have many facilities to begin with is that they were hostile to abortion and put up barriers to providing abortion services even before Dobbs,” said Caitlin Myers, an economics professor at Middlebury College. Her research focuses on the US abortion landscape, and she has been tracking travel distances to abortion facilities.

These states were more likely to have regulations like mandatory waiting periods and parental involvement that created challenges for people seeking abortions, as well as logistical hurdles for providers, such as those in Texas.

“This is basic economic theory,” Myers said. Strict regulatory environments created high costs to entry for providers, leaving space for only the few that could effectively scale their services up enough to survive, she said.

The Dobbs decision wasn’t the first time abortion clinics in Texas confronted their fate. About half of the abortion clinics there closed in 2013 when the state legislature passed a law that required them to meet hospital-like standards. The US Supreme Court overturned those restrictions, but dozens of doors closed remained shuttered.

“Having lived through that, I knew all the other clinics – the very few that were left – I knew they were going to close” after the Dobbs decision, Kleinfeld said.

By 2023, the total number of facilities providing abortions in the US was down to about 725, the UCSF data shows.

But each clinic closure has a ripple of negative effects, experts say, especially in regions where services have already been suppressed.

“We need every single abortion clinic in this country. There really aren’t enough for the number of people who need care,” said Nikki Madsen, executive director at Abortion Care Network, a national association for independent abortion care providers and other stakeholders. “When we treat abortion in an isolated way, we miss the broader cost of closing a clinic.”

About two-thirds of the clinics in states with bans have stayed open in some capacity, the UCSF data shows. Clinics often provide other reproductive health-care services and are sometimes the only touchpoint that people have with the health-care system.

“Independent clinics have always been based in their communities. They really understand the communities where they’re located and the people that they serve in those communities,” Madsen said. “So over this time, the clinics have been really working to figure out how they can continue to serve the same communities that they were serving pre-Dobbs in an increasingly hostile environment.”

Clinics move to the front lines

While some clinics have held their ground with a shift in focus, a handful of others have relocated into key access states or opened new locations.

“Providers are going to locations that place them as close as possible to the places where people are coming out of banned states in search of abortion,” Myers said. “They are primarily locating in places that put them on the front lines to receive patients, very strategically in southern Illinois, in New Mexico, in Virginia.”

The number of abortion clinics in New Mexico more than doubled post-Dobbs, rising from five in 2021 to 11 in 2023, according to the UCSF data. And the number of abortion providers in Illinois grew from 27 to 36 in that time frame.

Among the new additions is CHOICES Center for Reproductive Health, which relocated its abortion clinic from Memphis, where abortion is banned, about 200 miles north to Carbondale, a small city in southern Illinois. It still has a location in Tennessee that offers other services including birth control consultations and STI testing.

Red River Women’s Clinic had a much less distant – but no less significant – move. It popped just a couple miles away from its original location in Fargo, North Dakota, over the border into Minnesota.

“We were the only abortion clinic in North Dakota for over 20 years,” said Tammi Kromenaker, the clinic director. “We knew that if we didn’t do something, those patients who already drive three, four, five hours one way just to get to our clinic would face even bigger hurdles.”

Kromenaker says she had been exploring options to move the clinic out of North Dakota years before the Dobbs decision as a conservative state legislature threatened the clinic’s work, but options felt out of reach, mainly because they were too expensive.

But when the Dobbs decision leaked a month before it was handed down, the need to act instantly outweighed those concerns.

“It just was just this thing, like, ‘we just have to do this. We have to, no matter the obstacles,’” Kromenaker said, and she was thankful for a fundraising campaign that buoyed the clinic in that leap.

Struggle for solid financial footing

As clinics weigh their options in a post-Dobbs world, finances are the greatest determining factor.

“It costs money to close the clinic. It costs money to reopen the clinic. If patients have never gone to you for prenatal care before, it’s going to take time to develop a patient population who comes to you for prenatal care,” Madsen said. “All of these shifts really require community support and financial support from the community to continue to keep these clinics open.”

And constant changes to the abortion landscape in the US exacerbate clinics’ struggle for solid footing.

“I would have expected to see providers open in North Florida and North Carolina, which were both geographically important destinations after Dobbs, except for the fact that both states are fairly hostile to abortion,” Myers said. “The future there was so uncertain, and I think it was too risky to open.”

Before Dobbs, a 100-mile increase in distance to the nearest clinic could prevent about 1 in 5 people who wanted an abortion from being able to reach a facility to get one, her research shows.

Travel distance to abortion clinics continues to be a critical barrier to access, but a surge in virtual clinics has helped fill some of that gap.

In the last few months of 2023, about 1 in 5 abortions in the US were telehealth abortions, where medication abortions pills were mailed to a patient after a remote consultation with a clinician, according to a recent report from #WeCount, a research project led by the Society of Family Planning. By December, nearly a tenth of all abortions in the US – about 8,000 a month – were telehealth abortions provided under shield laws, which allow providers in some states where abortion remains legal to prescribe medication abortion drugs via telehealth to people living in states with bans or restrictions.

“Some people have resources to travel, but the pressure on brick-and-mortar clinics continues to build,” said Kirsten Moore, director of the Expanding Medication Abortion Access Project. “Now, patients can get their medications sooner because they don’t have to wait for a spot to open up in a clinic or find a way to get there. It’s vital.”

A Supreme Court ruling last week maintained broad access to medication abortion, but other ongoing legal challenges and ballot measures that will be on the table in a few states during this year’s election leave policies and planning very much in flux.

Although Red River has moved all of its staff and services to the Minnesota, Kromenaker has kept the address in Fargo to maintain standing in ongoing legal battles with the state.

“It would have been easy to just walk away and say, ‘OK, we’re going to sell this building. We’re done with North Dakota. We’re out,’” she said. “We have fought so long and so hard, we just didn’t want to give up. We’re just one little clinic, but downtown Fargo is still, technically, our corporate address so that we can maintain that standing in North Dakota and continue to fight for those patients we’ve served for … 26 years in July.”