Five years ago, in a wheelchair, Julia Hum was admitted to a state mental hospital in Massachusetts.

After treatment with targeted deep brain stimulation, she hopes to walk out soon and, for the first time in her adult life, live independently, in her own apartment.

Hum, 24, has severe obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD, which once caused her to hurt herself and even affected her ability to eat and drink.

“My OCD kind of convinced me food and drinks were contaminated,” Hum said. Her thoughts told her things like that her food had parasites or harmful chemicals.

“I was fully aware of how ludicrous these thoughts were, and I desperately wanted to gain weight and eat enough and drink enough and be healthy. But the doubts I had were just so loud,” she said. “They were screaming, and I couldn’t focus on anything else.”

Her heart rate and blood pressure became so erratic, she needed to use a wheelchair to move around. Doctors used a tube that led into her stomach through her nose to give her food and gave her fluids intravenously.

Now, after treatment, she’s doing much better. In August, she got her high-school equivalency diploma and posed for a photo with the certificate with a wide smile on her face. She’s no longer hurting herself, and she can eat and drink normally. She says intrusive thoughts are no longer in control.

“I feel like my OCD was kind of at the helm of the ship before, and now it’s kind of like a pesky passenger. It’s there, but it’s not taking over my life,” Hum said.

She and her doctors credit this lifesaving improvement to innovative research that allowed them to more precisely target a dysfunctional circuit with a device called a deep brain stimulator, which acts like a pacemaker for her brain.

Deep brain stimulators have been used for two decades for movement disorders like Parkinson’s disease and dystonia. More recently, their uses have been expanded to include mood disorders like depression and other neurological conditions such as Tourette’s syndrome and OCD.

The devices have two electrodes that target a pea-size structure deep inside the brain called the subthalamic nucleus. This node, which looks like a contact lens, contains more than half a million nerve cells.

It’s a hub for signals passing between the brain’s outer and inner layers. It’s like a switchboard, says Dr. Andreas Horn, a neurologist at the Brain Modulation Lab at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Doctors implant the electrodes close to the subthalamic nucleus and then adjust the settings through a pulse generator that is implanted under the skin of the chest. After waiting about two weeks after surgery to let the body heal, they turn on the electricity and adjust the settings to find something that feels good to the patient.

“I’ll suddenly feel lighter, my rituals will slow down, and I’ll sit up straighter and feel more energy,” as an example, Hum said.

Refining deep brain stimulation

Hum had a deep brain stimulator implanted in 2021.

Her psychiatrist, Dr. Darin Dougherty of the Mass General Research Institute, said it didn’t initially give them the results they’d hoped for.

“It was this kind of cycle where we would find settings that felt really good. They would work maybe for a month or two, and then I’d slide backwards again because the initial effects would wear off,” Hum said.

Deep brain stimulation can be life-changing, but it doesn’t work equally well for everyone, and researchers say they’re getting closer to understanding why.

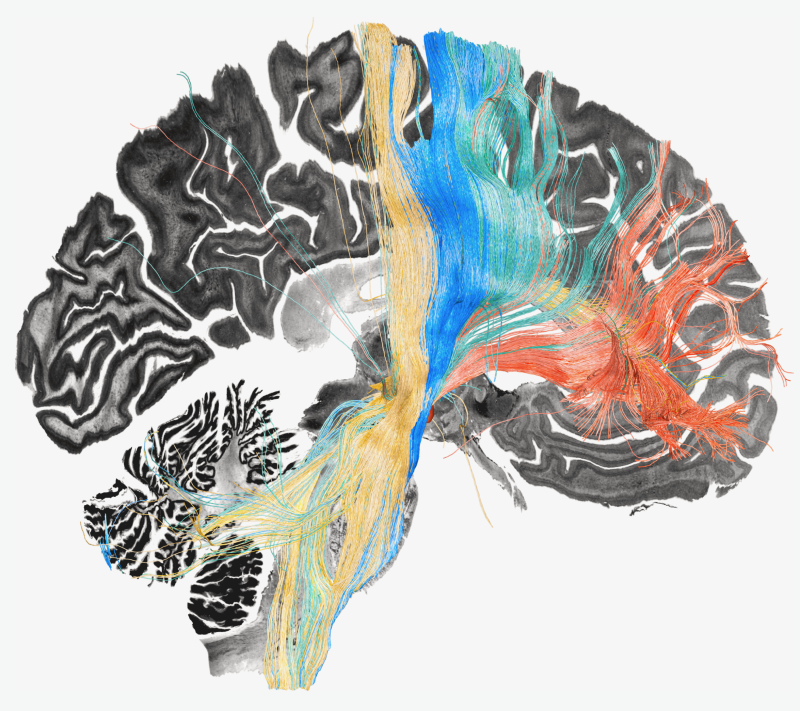

In a recent study published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, Horn and an international team of researchers took data from more than 530 electrodes implanted in the brains of more than 200 people living with four conditions: Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, Tourette’s syndrome and OCD.

They looked at where the devices were stimulating each person’s brain and how much improvement each had. Then, they used these records to map the nerve networks that seem to become dysfunctional in each of the four disorders.

“The idea is that by learning from a cohort of patients and contrasting who got better with the ones that unfortunately did not get as much better after treatment, we can pinpoint where the optimal site is and maybe the optimal network to stimulate,” Horn said.

The team used their maps to adjust deep brain stimulators for three patients, including Hum.

All of them saw substantial improvement in their symptoms.

Dr. Sameer Sheth, a professor of neurosurgery at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston who was not involved in the study, says that the research is encouraging because it uses data from a large number of people but that trying it out in just three people isn’t enough to know whether these brain maps are accurate.

“For the most part, this information has not been tested in the wild in a new set of patients, so that’s what this is setting up,” said Sheth, who also treats people with deep brain stimulation.

If the same good results can be repeated in more patients, “then we should act on it. We should implant with this type of profile in mind for this type of patient, let’s say a patient with OCD,” he said.

‘It gave me my hope back’

Using the maps created by Horn’s team and a special type of magnetic resonance imaging called diffusion imaging, doctors can see the fibers they need to stimulate to have the best chance of getting people well, Dougherty said.

Each electrode implanted for the therapy has multiple points of contact that doctors can use to stimulate different brain areas.

“We were then able to see which of those contacts was closest to the fibers that would be most likely to be helpful” for Hum, Dougherty said.

They made adjustments to Hum’s settings in August, and she says the difference has been night and day.

“It’s allowed me to focus,” Hum said. She notices that she can engage in therapy better, and she’s been able to create more distance between her thoughts and her actions.

“I was able to more accurately label a thought as OCD and really not me and choose to make the decision not to engage in a ritual,” she said.

She can also eat and drink “pretty much everything.”

When she got her deep brain stimulator, Hum says, “my very basic hope was just even to have any sort of life at all, and now it’s much bigger than that.”

She wonders if she can go to college, live independently and have a steady job. And she wonders about love.

“Can I have a solid relationship with maybe a boyfriend and just all the things that I’ve kind of missed out on till this point?” she said.

Hum said it’s hard to explain the gratitude she feels to the doctors and researchers who helped her.

“Hope had really gone. I didn’t see a future for myself,” she said. “It kind of re-lit that light and the end of the tunnel.

“It gave me my hope back.”