When Jessica Coletti’s 3-year-old son Vincent lost his usual pep last month, she worried that something was really wrong.

“Mommy, I’m not good,” the normally energetic boy told his mother one Saturday in early March. By Monday, the Chicago mom of two said Vincent was no longer moving much or talking.

“His eyes looked super empty,” Coletti said, describing her son’s eyes, glassy from fever. Vincent’s eyes were also red and he had a rash. He’d tested positive for Covid-19 at the time, but Coletti felt like something else seemed off.

The family’s neighbor, a nurse, came over to check on the boy and urged Coletti to get him to a hospital right away.

“It was definitely one of the scarier moments of my life,” Coletti said.

A couple of days after the 3-year-old’s hospital visit, the test results came back positive for a highly infectious disease that the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had considered officially “eliminated” from the US since 2000.

Vincent had measles.

Coletti lives in one of the 17 states that have reported outbreaks of measles this year.

As of April 18, there have been 125 cases, according to the CDC. Last year there were only 58 cases. The US generally sees about 72 cases per year, according to the CDC.

Most measles cases in the US happen when someone travels overseas to a country where the virus hasn’t been eliminated, but Coletti’s son hadn’t been out of the country. He wasn’t even enrolled in school yet. Most of the cases in Chicago this year have been connected to a temporary shelter set up for migrants, but he hadn’t been there either.

Coletti may never know how Vincent caught it, doctors say.

“Measles is so terribly contagious. You could be in line at a grocery store with somebody who had measles and catch it and would never know, because the measles virus hangs out in the air for so long,” said Dr. Claudia Hoyen, the director of pediatric infection control at UH Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland. Hoyen did not treat Coletti’s son.

Coletti said her son had been partially vaccinated, but he hadn’t had his second shot yet because he was too young.

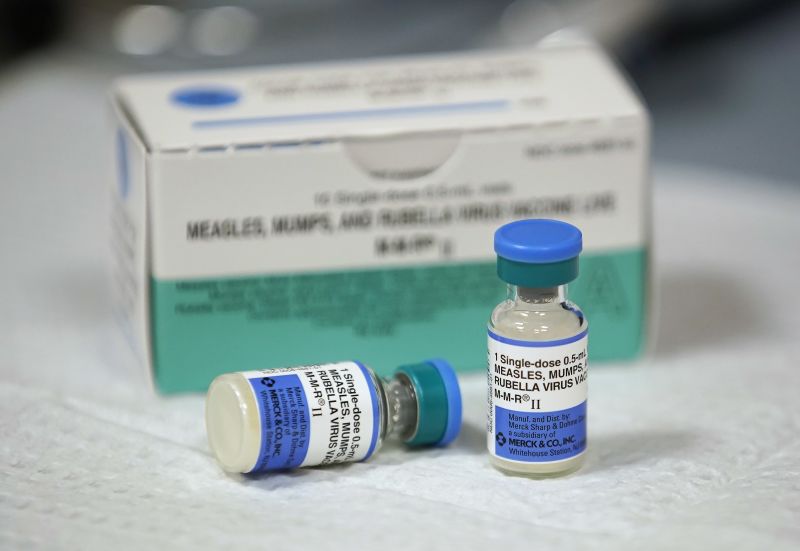

In the US, the CDC recommends that children get the first dose of the vaccine that protects against measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) between 12 and 15 months of age. Kids get a second shot between 4 and 6 years of age.

The vaccine for measles is considered highly effective. One dose is 93% effective against measles, with two it is 97%. Vaccinated people can still get sick, but it doesn’t happen often and typically it’s a milder infection.

“Little kids with the measles just look miserable. They do not feel well at all,” Hoyen said. But, she said, Coletti’s son was fortunate to have protection from even a single dose of the vaccine. Measles can be deadly for people who are unvaccinated and lead to even bigger health problems including encephalitis and pneumonia.

“Especially if he had Covid and measles at the same time. I would be worried that he might be someone who would be set up to get pneumonia, because he already had something affecting his respiratory tract, so it is a good thing he was vaccinated,” Hoyen said.

Coletti said they had a long wait before they were seen at a local hospital, but Vincent was admitted as doctors ran tests and treated him with IV fluids. A day later, the boy started feeling better and his rash seemed to go away, Coletti said, and Vincent was sent him home.

But that was not the end of it. The phone rang two days later and Coletti learned about his measles diagnosis.

It wasn’t just a sick kid Coletti had on her hands: She was inundated with other calls related to the virus.

Coletti said the Chicago Department of Public Heath called first, followed by her son’s doctor’s office. And then she got another call from the hospital where her son had been admitted.

“It was a doctor letting me know that my son was exposed to measles in the ER and I was like ‘no, my son is the one who exposed your ER,’ ” Coletti said.

Although her son started to feel better by the end of the week, the CDC recommends that people who are sick remain in isolation for four days after the onset of the rash because the virus is so contagious. People with measles can infect others from four days prior to the rash and four days after, studies show. The virus can stay in the air for at least two hours after someone with the measles leaves the area.

Because Coletti’s infant daughter was too young to be vaccinated, Coletti worried she would test positive for the virus, so the whole family had to stay at home. The health department also told her that she and her husband had to stay home from work until they could prove they weren’t sick and had been vaccinated.

“The nightmare wasn’t just that my son was sick. That was horrible, but then it’s your whole world. You can’t go to work. You can’t do this and that, and you can’t even believe it,” Coletti said. “You never think it is going to happen to you, but until you are dealing with all those phone calls trying to figure out what’s going on and tracking the last 21 days of your life so they could try to link you to someone else that has it. It’s more than what you think. People don’t realize how much goes into it.”

Any time someone tests positive for measles, public health departments try and contact trace anyone who may have come into contact with that person to help stop the spread.

Blood tests eventually showed Coletti and her husband had protection from vaccination.

Dr. Frank Belmonte, the chief medical officer and chairman of Pediatrics at Advocate Children’s Hospital in the Chicago area said that with the recent outbreak of measles in the city, hospital staff has been doing a lot of mitigation efforts. The city has seen 63 cases so far this year.

Belmonte said Advocate Children’s Hospital tries to be proactive. Workers go through patient records to see who is behind on their vaccines and call people to encourage them to get up to date. They’ve also done education and outreach efforts about measles in the community in a variety of languages. And because measles had been so rare, they have also had to train staff to recognize the symptoms.

“We’ve also done a lot of education with our physician community, telling them to be on the lookout for the symptoms and to understand what the rash looks like,” Belmonte said. “A lot of this generation of physicians either only saw it very rarely or never saw a case of measles.”

When his hospital has a case, Belmonte said they call anyone who may have been exposed, as well as figure out a plan for those who could get sick.

“We’ve learned a lot during Covid about how to do this and how to work well with our state and local public health authorities and I think we’ve used those techniques and applied it to this particular situation with measles as well,” Belmonte said.

Hoyen, with UH Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital, said health care systems need to have a heightened sense of awareness when there are measles cases in the community. For example, even when Cleveland didn’t have a single case of measles last summer, hospital staff knew to ask patients if they had traveled to Columbus, Ohio, when that city had an outbreak.

“Kind of like what we were doing with Covid, to help screen people out — again, because measles is so terribly contagious,” Hoyen said.

Hoyen has been concerned about the trend in lower vaccination rates among kindergartners in the US, but she hopes recent education efforts will help people understand why they should get protection.

“Whatever we can do to get people to understand that it’s not just a rash, it can be pneumonia or it can be encephalitis and you can die,” Hoyen said. “You don’t want to put kids at risk for this.”

Coletti saw what a “mild” case looked like with her partially vaccinated child and said she wouldn’t wish that on anyone.

“It was a lot at once,” Coletti said.