The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced Tuesday a $5 million initiative to offer seasonal flu vaccines to livestock workers in order to reduce the public health concern that a new version of the influenza virus could emerge among farm workers who are at a higher risk of catching the bird flu (H5N1) virus, which has been circulating in millions of farmed and wild animals.

The goal of the initiative is to protect the health and safety of livestock workers as seasonal respiratory viruses begin to circulate, Dr. Nirav Shah, principal deputy director of the CDC, said Tuesday.

“Preventing seasonal influenza in these workers, many of whom are also potentially exposed to H5N1 viruses, may also reduce the risk of new versions of the influenza A virus emerging,” he said.

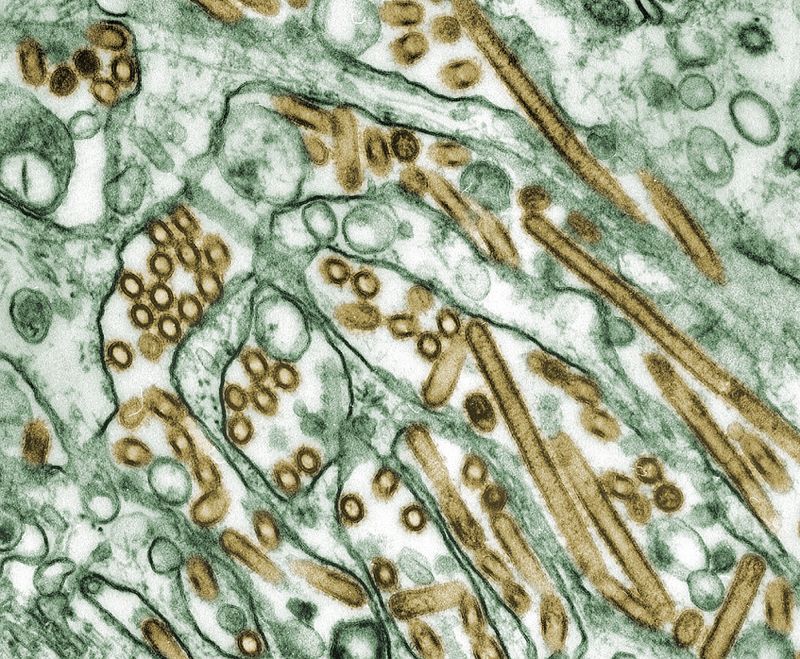

If two different strains of influenza infect a person, there is always a risk they could mix together and create a completely new virus with traits from each one. A new virus could be harmless, but there is also a chance that it could be even more contagious, deadly or resistant to existing treatments.

The risk of what is called genetic reassortment – when multiple viruses coinfect a cell and replicate to create a new virus – is “theoretical,” Shah said, but “because we know that it could happen, we want to take steps now to reduce that effect.”

“Anything that is predictable is also something that’s preventable,” he said.

Reassortment has happened with other influenza viruses. In 2009, H1N1 – which Shah described as “a close cousin” of H5N1 – was thought to have emerged because of genetic reassortment of influenza A viruses in pigs.

“I’m not suggesting that it was a human-pig interaction that led to that reassortment, but it was thought to be a reassortment-type event between a novel H1 virus and a more seasonal variety,” Shah said. “This is something that has occurred, and it’s a concern for that reason. Anything we can do to reduce the likelihood that a new virus that emerges that has the transmissibility of seasonal flu with the severity of H5 is a risk that we want to reduce as much as possible.”

The CDC said that under the new initiative, the seasonal flu vaccine will not be mandatory for farm workers. Public health officials at the state level will bring vaccines to workers at local events and to areas where they typically gather.

“This is fundamentally an effort that relies upon trust, and that trust relies upon us making the case for why the vaccine is important,” Shah said.

The seasonal flu vaccine does not provide protection against bird flu. The CDC says it does not think a specific bird flu vaccine is necessary, even among workers who are at a higher risk because they work with infected animals.

Although there have been additional bird flu cases in humans in this outbreak, Shah said, symptoms have been mild, and the prevalence is still “extremely low” and does not warrant an H5-specific vaccination.

The CDC says an additional $4 million will be sent to the National Center for Farmworker Health to help prevent more workers from getting sick with bird flu. The federal organization will use the money to partner with community-based organizations in affected states. Together, the organizations will provide training and information sessions about bird flu and expand access to testing, treatment and personal protective equipment.

The CDC said Tuesday that there have been nine known human cases of H5N1 among poultry workers in Colorado related to the latest outbreak.

Officials previously said that the workers who got sick had been culling poultry believed to be infected at a farm in the northeast part of the state.

The latest human cases are mild, mostly involving pink eye or conjunctivitis. The CDC said there are no additional tests pending, but there still could be additional cases.

There have been a handful of cases in other states, including in Texas and in Michigan. All were among farm workers.

The general public’s risk from bird flu still remains low, according to the CDC, but there is still a real risk for animals. The outbreak has affected millions of animals, with outbreaks in commercial poultry and in back yard flocks, cows, wild birds, wild mammals and even pets, mostly cats.